The Incident

In spring of 2017 a regular cycling companion, James, and I agreed to go for a road ride. Opportunities to get out are not easy to find, both of us having young families and commitments to ferry them about in our cars and it’s nice to get out of the driving seat sometimes. The weather on the day of the ride was as good as is can be that time of year, bright and dry. We met in Cuckfield and set on our way, following minor roads to Cowfold where we had to use the A272 to get towards Partridge Green, where we intended to stop at a café. As we headed westbound out of the village past parked cars I heard a car horn sound from far behind me. The cars immediately to my rear seemed innocuous so I reasoned that whoever had sounded the horn was some way back. As we rode out of the village two cars passed me, then a van followed, passing extremely closely. I was startled; I watched it pass James ahead of me, similarly close. Then the driver stopped the van in the middle of the lane, blocking us and the traffic behind us. He got out of his vehicle looking agitated. I took out my phone and started taking a video on my phone, in part as a defence and in part as a record.

I filmed him walking down past the side of his van; he visibly changed posture when he saw my phone held up, and began shouting at us. “You hit my van!” he started, what followed was a stereotypical debate about road funding; I tried to tell him about Highway Code Rule 163. During the exchange I learned James had palmed the van as it passed, a familiar act for anyone used to regular close-passes intended to let the driver know they’re too close. We continued to remonstrate as he returned to his van, and as James and I passed him, keen for the situation to be over and to escape the area.

As I rode on I was about to stop the video recording and return my phone to my pocket when I heard him accelerating behind me, I held the phone and my handlebar in my right hand as he overtook me again, closely. I decided to continue to video him overtaking James. James had adopted the primary position, occupying the lane as the road turned a gentle corner. The van approached him and the horn sounded, long and loud, James held his position and the driver forced his way around him, and then he swerved sideways into James, forcing him past a low concrete bollard onto the grassy verge, a less competent cyclist could have been pushed off the bike or under the wheels of the van. I stopped the video.

We stopped at a café to regroup mentally and discuss what had happened. I resolved to report the incident to Operation Crackdown that weekend.

The Reporting

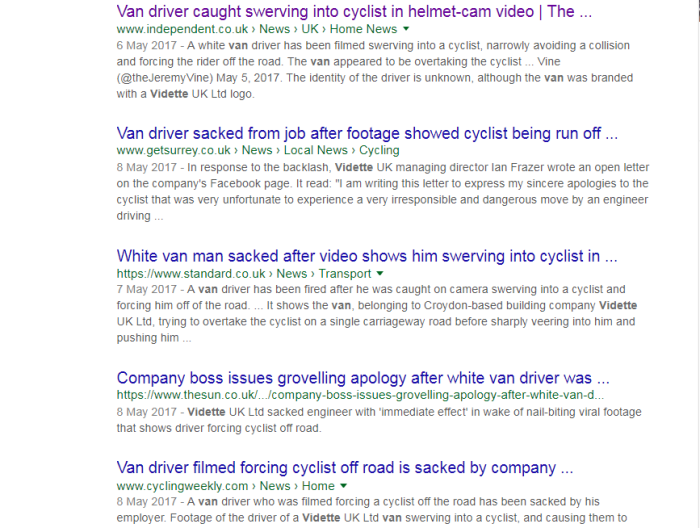

The Operation Crackdown online form asked for any supporting video evidence to be uploaded to a sharing site, it suggested YouTube, so I did that, being careful to make the video unlisted. However unbeknownst to me it was soon picked up by a Facebook page called “Idiot Drivers Exposed”. I only found this out the weekend after the upload when James saw the video on Road.cc. The video had gone viral, from Facebook to UK national press and local television news to popping up on news websites all over the world. I was contacted by journalists on Twitter. This was not what I wanted; I wanted to see our justice system in action, not the unpredictable vitriol of social justice. Fortunately I’d cropped the video to exclude the section showing the driver’s face, but the brand on the van he was driving was clearly visible and the bottom half of the internet was in full-swing. Jeremy Vine ran a feature on BBC Radio 2 and a local BBC radio service had to apologise for proposing a feature which suggested James might have been at fault. I felt for the company director who was receiving ire for actions which were not his own; I soon learnt he had sacked the man driving the van.

The next day I received a phone call from a Sussex Police Traffic constable asking if I wanted to press charges. He told me that the charge would be dangerous driving, more serious than assault and carrying a minimum driving ban with the possibility of imprisonment, and if I wanted to go ahead I would need to confirm quickly because the charge must be issued within two weeks of the incident. I checked with James, and we decided to go ahead.

James and I were invited to separate appointments to make statements and gather evidence for the case to be raised to the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) for review. My statement took 3 hours; the officer was friendly, encouraging and meticulous in what he wrote. He mentioned how frustrating it was for the police to try to provide adequate cover to Sussex highways; that there were only three officers patrolling the whole region that evening. He was enthusiastic about getting CPS support and a conviction to follow. My statement reached 5 A4 pages. James revealed to me later that his reached 4.

A week later we were informed that the CPS felt the case had sufficient merit, public value, and quality of evident for them to prosecute. Had they not, James and I would have had to fund the case ourselves. It was at around this time I realised that if I had relied on Operation Crackdown alone, and had the video not gone viral, the Police may not have picked it up in time to notify the vehicle owner and the CPS may not have placed sufficient value on the case to prosecute. I was told that the driver having lost his job as a result of the publicity could provide mitigation for him if he were to be found guilty.

A few weeks later we were told that at the preliminary hearing, the driver had pleaded not guilty, and therefore James and I would have to stand as witnesses at a full adversarial trial, with cross examination by the counsel for the defence and a magistrate passing judgement.

The Court

Some weeks passed before our court date was confirmed. We were contacted by the Witness Support Service, who offered a tour of the courtroom to us before the case would be heard. Apprehensive of what was to follow, we took this up. The witness service is run by a group of (excellent) compassionate volunteers; I also learnt that even the magistrate is a volunteer with no legal training.

Our court date arrived and James and I turned up at the court, suited and nervous about seeing the man who had aggressively driven his vehicle at one of us. The counsel for the prosecution introduced herself to us and let us know there might be a wait. We were given copies of our original statements to re-familiarise ourselves with the events of the day, since some months had now passed. We whiled away a couple of hours in the witness room alongside other witnesses for other cases before we were informed our case would be postponed. A higher priority domestic violence case was going to take longer than planned, so there was insufficient time to hear ours. We agreed a new date with the court service and went home. As we left the court building we saw a local TV crew standing outside the court, following up on the case after the viral coverage earlier in the year.

Three more months passed before the new date came around. This time we were told that, as a matter of policy, our case would not be postponed again. We arrived, went through security and were seated in the witness room. A different counsel for the prosecution introduced himself and made sure we were comfortable and understood the order of proceedings. He disappeared for ten minutes, when he returned he told us the accused had changed his plea to guilty, meaning James and I would not need to stand as witnesses after all. We could sit in the public seating in the courtroom to watch the sentencing though.

We walked to the courtroom and sat next to our companion from the witness service. The counsel for the prosecution began presenting evidence and showed the video I had taken. I watched the exchange between the three of us, the argument, and my parting shot of “Rule 163! Learn the Highway Code, learn to overtake safely!”. I winced as the van sideswiped James into the verge.

The counsel for the defence then began their case. He hinted at prior convictions for the driver, seemingly some were violent. He focussed on mitigation of potential sentencing; the counsel reasoned that given the defendant’s history, he did well not to get violent and as such some leniency should be given. We also learnt that he had two young children who lived some way away and his fortnightly visiting rights meant he would need a car (despite a direct train line between his and their homes, I thought to myself). When both cases were heard, the magistrate and his two legal advisors left the room to deliberate.

When the magistrate returned, he asked to re-watch the video. We sat through it once more, and the magistrate began stating his interpretation of the evidence. He acknowledged the content of Highway Code Rule 163 and that it had been breached. By the context in which he spoke, I realised he would not have known about the rule had I not shouted it in the video; nobody else in the courtroom had mentioned it. He then went on to suggest that, by adopting the primary position, James may have aggravated the situation; nobody in the proceedings had mentioned that this is good practice and that it was completely legal. He also suggested that because James and I had been cycling one behind the other we had been “cycling in a way that would not obstruct normal overtaking”. The more he spoke the more I realised he didn’t know about safety and the law.

The magistrate began concluding and sentencing, he said the defendant had been convicted of over 40 previous offences, some violent but only one driving related for mobile phone use, and nearly 30 court appearances; he had got out of prison in January and was due to meet his probation officer the day after the incident. I watched the defendant as the magistrate went on; he noted the defendant’s social and family situation and acknowledged that he had not been violent. He was guilty of dangerous driving under Section 2 of the Road Traffic Act 1988, the sentence was 160 hours community service reduced from 180 hours plus an 18 month driving ban with a requirement for an extended re-test plus court costs. The ban and costs appeared to be perceived as the most punitive part of the sentence by the defendant. He protested that he wouldn’t be able to visit his children, he said he’d lost his job that morning when he’d told his employer about his court appearance, and he said he wouldn’t be able to afford his phone contract. When he was asked by the court how he could be contacted for payment he claimed to have no landline, no mobile phone number, and no email address. We learned he already had an assigned parole officer since he’d been released from prison earlier in the year. As the means to obtain payment of costs concluded, James and I left the room with the witness service representative.

As we left the courtroom the witness service representative called the defendant a recidivist; he won’t learn from being punished for his actions. As we walked through the foyer to leave the building, I didn’t notice the defendant seated nearby; he shouted “you ruined my life” at us as we passed. I turned and considered my response but said nothing and walked away.

James and I left the building and began to get into James’s car, we were about to leave when we saw a news camera pointed at us from a few metres away. We waited as a journalist ran towards us and we introduced ourselves. We were asked if we were happy with the conviction and that it would be on ITV local news that evening. James told the journalist his feelings on the case and asked not to be identified, fearful of recriminations from the potentially vengeful convicted man who was at that time walking out of the court building towards the train station. We said goodbye to the journalist, got into James’s car, and left.

I had mixed feelings about the experience at that time. I accepted the necessity for the adversarial system and that it would inevitably be nerve wracking. I accepted that the defendant should be trialled for this case alone, but his prior violent convictions being used to mitigate his sentence seemed contradictory. I was surprised how little the magistrate knew about the law, several people that day said that all magistrates have no legal background and often make seemingly unfair decisions and take more flak from defendants than a professional judge. I realised that if I hadn’t shouted “Highway Code rule 163” in the video the outcome of the case could have been less in our favour, and next time it might serve me to shout “he’s adopting the primary position for his own safety in accordance with government guidelines on good cycling practice!”

James has told me that he didn’t appreciate hearing the counsel for both the prosecution and the defence misleadingly referring to the primary position as “the middle of the road” during the hearing, the middle of the road is where the white lines that divide opposing lanes are. Given that we were cycling well in excess of 10 mph, he was disappointed the prosecution didn’t indicate that the driver shouldn’t have overtaken on a solid white line, as was the case during the first dangerous vehicle manoeuvre, which lead to the reason for adopting the primary position and the sideways swerve incident. He’s ridden his road bike less since the incident, being slightly more nervous around traffic. He’ll probably get over it in time.

At least the magistrate didn’t start talking about road tax. An eye-opening experience: thanks for sharing.

Very intresting i well remember that video when it first appeared, and thankfully you both didnt suffer any physical injuries, just sometimes the law works.

He’s been ruining his own life for a very long time having had 40 prior court convictions.

How driving a 2 ton vehicle at a person cannot be seen as violent behaviour is beyond me.

A lot of people would have been daunted by the experience, so thank you for following this up in the legally correct manner.

Thank you for sharing this story, meticulously told – and thank you both for pursuing this case such that we might all be better off in the future. It sounds like quite an awful experience, made worse perhaps by lack of understanding in the courtroom – but fortunately a just outcome in the end. I hope this inspires others to similarly pursue other cases.

I think the most appropriate response to ‘you ruined my life’ would have been ‘yes, well you nearly ended mine’…is what I meant to say.

Unlisted doesn’t prevent it being found in searches. It just means it isn’t shown to others viewing the videos in your channel. What you need to set it to is ‘private’ ie. only those who have the link can view it.

Thank you for writing this up. Certainly an interesting insight. Sorry that you both had to go through this whole experience and I wish you happy cycling from now on.

Thanks for the tip!. I use my camera to record close passes but have had very little success in getting prosecutions, so will yell “Highway Code rule 163” next time. How dare the driver yell “You ruined my life” when he almost ended James’s and yours – just typical of the toxic nature of Britain’s roads. Truly the law is an ass when it can neither recognise assault with a vehicle nor the perils of adhering to best practice. Good luck to you and James and please don’t let this put you off cycling